Arthur Young And Pirsig:

Can Young help us to understand the levels?

By David Morey

The object of this essay is to introduce MOQers to the work of Arthur M. Young and his book "The Reflexive Universe" (Delacorte Press 1976). In this work Young looks at cosmic evolution and proposes his own theory of process. It is my view that his examination of the relation between time and structure adds to what Pirsig has to say about dynamic and static quality. Young also has his own version of levels that may clear up some of the problems with respect to Pirsig’s suggestions.

Young points out that structure cannot refer to the activity of time, that it describes a ‘system of relationships’ and is therefore static in Pirsig’s sense. A clear distinction needs to be made between ‘an act in process’ and ‘an act completed’. Introducing time and process is the difference between still pictures (structure) and a moving film.

Young begins his examination of cosmic evolution with the strange world of quantum particles, full of opposite pairs that seem to imply the nothingness from which they come.

Young refers to the assumption of science that it discovers laws which it holds as sacred. Law implies restriction and limitation. However, the value of this ‘law’ is that it provides some certainty and therefore becomes the means of achieving ends. If there is a value to SQ and a purpose to the cosmos, surely Young is looking in the right place. In as far as we can assume A causes B then determinism is an opportunity to expand our freedom rather than reducing it. Young, as an inventor, always suspected that if you were ever going to get a design to work you had to have a purpose for which you were aiming.

Young suggests that all processes go through seven stages and notes that many myths about the creation of the cosmos go through seven stages.

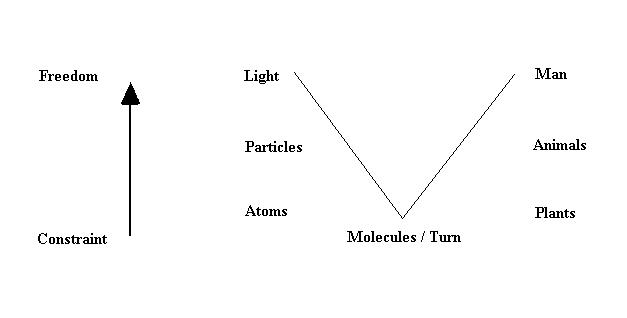

The seven stages are represented by seven levels being: ‘light, particles, atoms, molecules, plants, animals and man’. Also clear how the higher level needs the levels below to exist.

Young begins with light that is without mass, that travels at a speed where time does not exist, is pure energy and to this extent non-physical.

Young also aims to sub-divide the seven levels by seven. Such as the seven periods of the atomic periodic table. He also suggests that the final stage of each group of seven is able to complete the process and attain dominance over the lower stage and is therefore in possession of greater freedom, e.g. DNA in relation to organic molecular processes.

The relationship with Pirsig’s dynamic quality is very close. Young describes quantum of action (light) as having three degrees of freedom and none of constraint. The process of evolution then requires freedom to be given up and constraint (physicality) to be taken on. After light, particles have two degrees of freedom and one of constraint. This is the realm of ‘probability fog’.

The introduction of mass is the degree of constraint. At this level the appropriate science is that of electro-magnetic fields rather than mechanical concepts of matter in motion. We can then see how atoms are more constrained than particles, and the combination of atoms, i.e. molecules, are the most constrained of all entities.

It is the science of molecular bodies and materials that gave us the billiard ball notion of mechanics in the first place. It is the lack of dynamic freedom possessed by molecules that make them the ideal ‘object’ of scientific study. Determinism was a theory that came out of the study of this particular level of non-dynamic (non-free) entities.

For Young, this represents a kind of fall from the unrestrained freedom of light to the certainty and constraint of molecules. The next point is, of course, to suggest that the levels of plant, animal, man build on this certainty to achieve progressive levels of freedom that are unique to them. DQ goes on a journey, sacrificing itself to SQ so as to produce a level of physicality and existence with the potential to organise itself to obtain a high level of DQ in a context of SQ physicality. From nothing to something and back to nothing it might be suggested. A cosmos that is a form of self-expression where the artist has had to create her own materials. What is mass if not the expression of restraint? What are static patterns, if not the withdrawal of dynamic activity for the sake of endurance and the same again? And why the same again, if it is not because the same again seems to be of value. Young points out that science developed the notion of laws in relation to inert objects, in which many particles are combined to cancel out their natural agitation (activity). Amusingly Young suggests Galileo would not have got far with his theories if he had dropped birds! Also interesting to note that it is the agitation of particles that accounts for their ability to occupy the vast empty spaces of the atom.

It is also a great wonder how such different atomic properties arise from the different combinations of protons, neutrons and electrons that make up the different elements. To return to particles, it needs to be realised that the uncertainty with respect to their behaviour is ontological and not simply epistemological. The location of an electron can be known only through interacting with it (an event) its motion has to be described in terms of probability fields. Probability implies freedom or even choice. The electron has a given set of possibilities where it might turn up. This is key to movement over time and process. It is only with respect to the past, to a snap-shot, to an event, that we can speak of an electron as having a location in space. Structure implies relationships at a moment in time, as if time could be stopped, and freedom, movement, process did not exist. These are the reasons why DQ is a problem in terms of analysing it. Young draws an important analogy between the behaviour of particles and the freedom of human beings. It is well known that when science tries to describe either of these entities it has to rely on statistics because the only possible patterns apply to the group but not the individual, as any insurance company or particle physicist will confirm.

Young’s theory of an initial descent from freedom to static structures has three levels. Young suggests that this may be similar to the fact that you would need three fixed ropes to pin down a wild animal.

Matter for Young is the containment of motion. The free moving photon losing some freedom when captured in a spinning particle, is further reduced when that particle is bound to other particles in an atom, and truly fixed into position in the grid of a crystal.

Giving three steps from freedom to determined entities. To climb back up to freedom will therefore be three steps in the opposite direction.

Young also notes for the three stages of descent there is both a move from the homogeneity of the photon to the complexity of molecular combinations, and from high degrees of energetic uncertainty to the certainty of energy in the contained form of matter.

It is only at a very stable level of matter, within a small temperature range that it is possible to build the molecules required to build living organisms.

Next Young points out the connection between constraint and symmetry. Highly constrained levels have full symmetry such as crystals. Plants have the freedom to grow and therefore lose their symmetry from top to bottom. Animals have more freedom of movement and also lose their symmetry front to back. It is quite easy to understand that full restriction relates to full symmetry: front to back, left to right, top to bottom.

It is also interesting to note how human left/right symmetry is not perfect in the face, in handedness, and left/right brain function.

Young draws out his scheme thus:-

Complexity increases from light to molecule to man but the important thing is to see that freedom reduces from light to molecule but increases after the turn from molecule to man.

I hope this brief essay will lead my fellow MOQers to take a look at Arthur M Young’s work as I think it offers new insight into the concept of levels. A more detailed and better constructed argument will be found in Young’s The Reflexive Universe, (Delacorte Press 1976).